In novels, screenwriting, and play-writing a scene is a useful structuring device for deciding what happens, where, to whom, and why. There are many ways to outline a story, but planning scene by scene is a useful way to make sure every scene has purpose, intrigue, and the other ingredients of a great read.

Here are 5 tips to plan and link individual scenes to create structured story arcs:

1. Start with what you want your scene to reveal (purpose)

Telling a story is a process of revelation, as well as of concealment. We reveal what we want the reader to know (about characters, situations, intrigues, threats, and more). And we conceal

some information (to create mystery – or because we don’t know all the answers yet ourselves!)

When creating scene summaries to organize and guide your story’s draft, ask:

- Why is this scene important? (‘Because it shows/tells/explains/teases …’)

- What does it introduce that makes the story more interesting (e.g. new characters, goals for existing characters, obstacles, surprises)

Let’s briefly examine purpose in a scene by a master of plot, John le Carré:

Example of finding a scene’s purpose: The Spy who Came in from the Cold

In le Carré’s classic Cold War spy novel, the opening chapter titled ‘Checkpoint’ begins with a scene where a British agent, Alec Leamas, is awaiting the arrival of a double agent:

The American handed Leamas another cup of coffee and said, “Why don’t you go back and sleep? We can ring you if he shows up.”

Immediately, we have an interesting situation – characters waiting for another person, late in the night.

Le Carré creates further intrigue:

Leamas said nothing, just stared through the window of the checkpoint, along the empty street.

“You can’t wait forever, sir. Maybe he’ll come some other time. We can have the Polizei contact the Agency: you can be back here in twenty minutes.”

“No,” said Leamas, “it’s nearly dark now.”

“But you can’t wait forever; he’s nine hours over schedule.”

After more pushing from the second man at the checkpoint, Leamas snaps:

“Agents aren’t airplanes. They don’t have schedules. He’s blown, he’s on the run, he’s frightened. Mundt’s after him, now, at this moment. He’s got only one chance. Let him choose his time.”

Thus the scene reveals:

- Who key players are in the story (Leamas, the unknown man whose cover is blown, and some person called ‘Mundt’ who is after him)

- A key unknown or point of tension for further development: Whether or not the man will make it to the agreed checkpoint

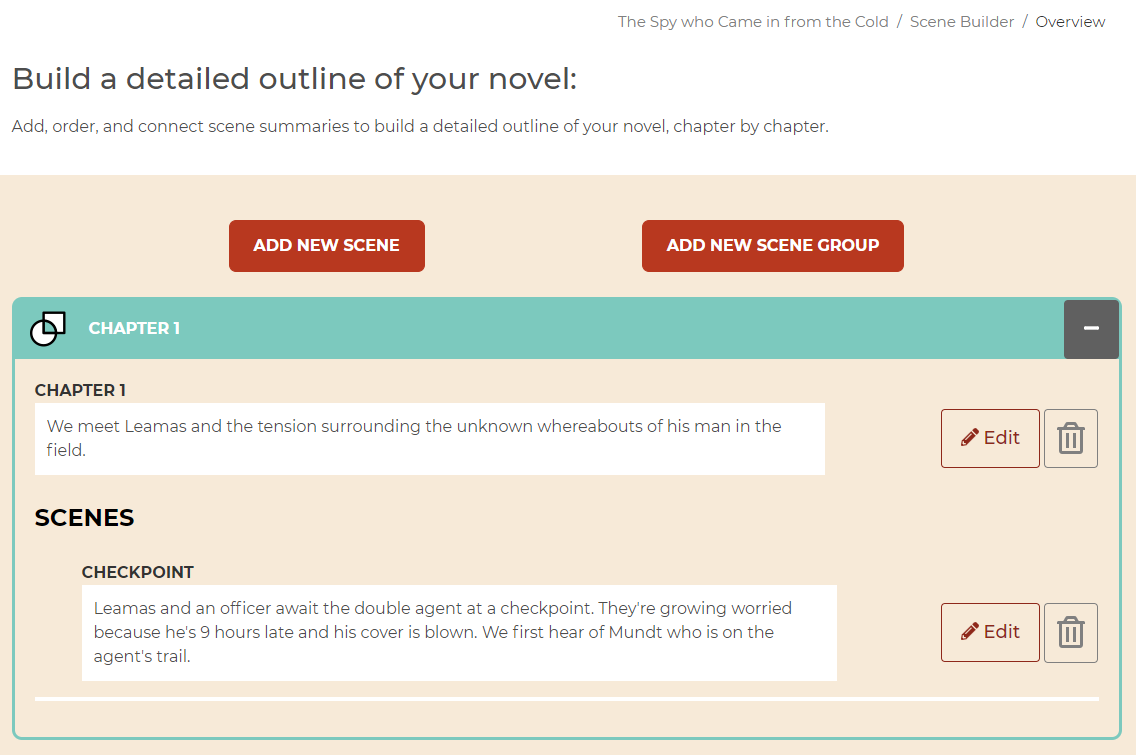

We could summarise this scene thus, if we were le Carré and at the scene planning stage:

2. Decide conflicts or unknowns to plant in your scene

Conflicts and unknowns in storytelling are like seeds that you can plant, to grow into ordered, tidy events or tangled, thorny messes. What comes next, once you know the purpose of a scene, how it relates to your characters’ desires, fears or goals?

Think about conflicts or unknowns that will give you something to develop in coming scenes and chapters.

For example, in the scene and chapter summary above, we see le Carré’s given readers:

- Unknowns: We wonder who exactly Leamas is waiting for and how is he connected to Leamas (and vice versa). Keep in mind le Carré has not, at this point, revealed the man’s role or identity to the reader

- Conflicts: There’s external, implied conflict in Leamas’s words that Mundt’s ‘after him, now, at this moment’. This gives immediate tension

Further unknowns include questions such as: ‘Will the man they’re awaiting show up?’ or ‘Will Mundt get him before he makes their meeting?’ The implied conflict could spill out in further scenes, for example, a switch to the agent’s POV as he tries to avoid Mundt’s onslaught.

Once you’ve planted these seeds of story development, it’s easier to keep summarizing subsequent scenes. What will they reveal? And conceal for now?

3. Think about who your scene will involve

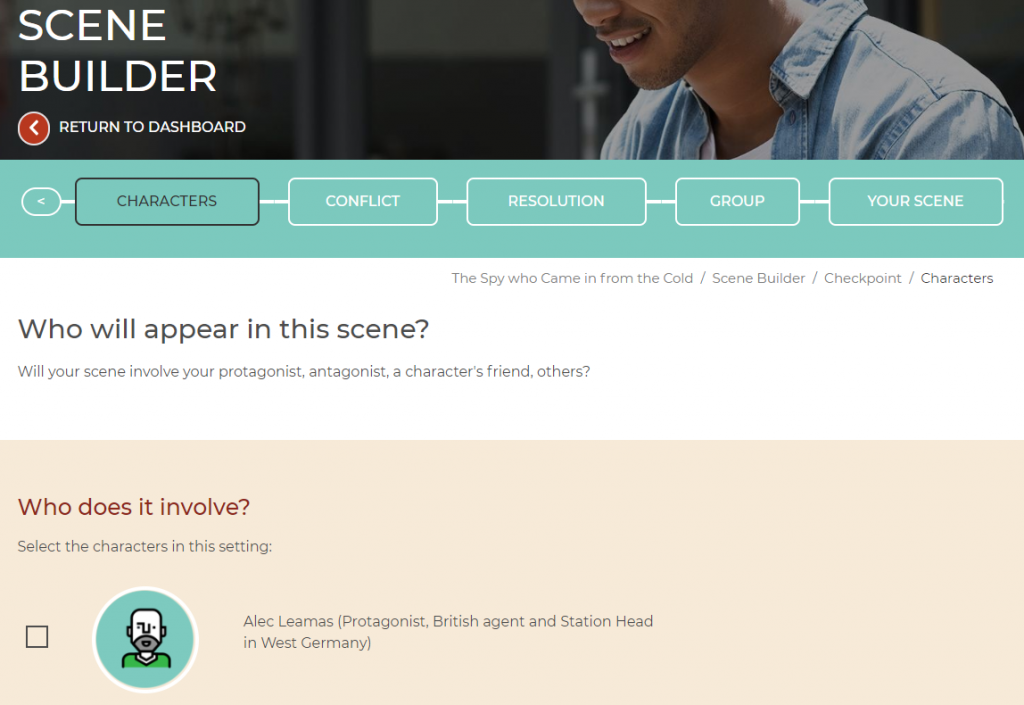

An important step in how to plan a story in scenes is deciding who will appear in what scenes.

This is an especially important consideration in scriptwriting and playwriting, as characters have different shares of time on-screen and on-stage (so every secondary part has to really count and be enticing to an actor).

When you summarize your scenes, think about opportune moments to introduce characters who fulfill important roles such as:

- Villain or antagonist

- Friend or helper

- Teacher or guide

- Lover

- Rescuer

- Ward

Some genres, of course, need these ‘types’ more than others. In literary fiction in particular, roles aren’t always clear-cut. Even in popular action stories, a hero might turn out to have villainous aspects (and the villain might be more human than we first thought).

Still, at least vaguely planning where in your story different characters appear (and how this will affect things like other characters’ goals, fears and obstacles) will help you plan new story intrigues and excitements.

You can also assign characters ‘role’ types in the ‘Characters’ section of Now Novel’s story dashboard based on their title or function, e.g. Leamas’ role as ‘station head’:

4. Brainstorm further developments

Once you know what the key function of a scene is, creating more scenes is a matter of asking questions. Ask questions such as:

- What if? (E.g. ‘What if the man Leamas is waiting for were captured (or even shot dead) by this Mundt guy?)

- What else? (E.g. ‘What else is riding on the man making it to Leamas in time? Is there another tense situation urgently needing the man’s input/skills?)

- Who else? (e.g. ‘Who else besides Mundt has an interest in the awaited man? Who all could he be serving/playing?

Curiosity is a major part of the storytelling process. We have to be curious about characters and their situations. What else could go right, and what else could go wrong? What’s the worst-case scenario, and the best? [These questions are key steps in the ‘Core Plot’ section of Now Novel’s story dashboard.]

If you’re adding a scene to your outline that starts a new chapter, also ask ‘who/what could this scene circle back to?’ Another pleasure of reading a great story is the way narrative circles and echoes what’s come before, as we encounter familiar faces, places, and questions.

5. Group scene ideas into larger units

It makes sense to outline at a scene-by-scene level and then only find the larger units of your story (your chapters, story arcs and other organizing larger ‘chunks’). This way, you can find the linear developments of your story, and later decide how you will chop and change between events, characters’ viewpoints and scenes.

In the Scene Builder tool on Now Novel, for example, you could group your scenes into chapters, or you could organize them according to arcs (naming each group of scenes with titles such as ‘Leamas’ Arc’).

The point here is that planning and structuring a purpose-driven story doesn’t have to be a bore. Creating a skeletal structure for events can be as much fun (and as creative) as the adventuring of drafting, where you give your reader the more detailed, blow-by-blow account.

Create structured scene and chapter summaries and connect them to form a detailed outline in the Now Novel story dashboard.

4 replies on “How to plan a story in scenes: 5 steps”

All good stuff but the Nocenti quote is MONEY. Thanks for sharing.

Glad you like it! Quote is true for a lot of Marvel’s work which Nocenti edited – action-focused with slower character development.

I love writing stories and creative writing is the the best

Good to hear! All the best with your writing.